Article | Tribute: K-3000 Snowgun

This is an article that appeared in the 2017 issue of 4241′ Magazine. Click on the image to read it online at Issuu, or read the text below.

Tribute: K-3000 Snowgun

Like a fine wine, this workhorse just gets better with age

by Dave Young

When Killington Resort successfully hosted the 2016 Audi FIS Ski World Cup at the end of an unseasonably warm and snowless November, it was an accomplishment made all the sweeter by the fact that Killington was the only resort in North America that could have hosted the event that weekend; there was simply not enough snow anywhere else. That Killington’s Superstar was the lone trail on the continent to feature a World Cup-worthy surface that late-November weekend came down to several factors. Sure, there was a little bit of luck involved, but you could also say that Killington’s Mountain Operations Team made its own luck, through hard work, smart strategy, and applying the right tool for the job. In that particular case, the right tool happened to be a slightly obscure piece of 1980s snowmaking technology known as the K-3000.

Few outside the tightly-knit community of professional snowmakers have heard of the K-3000, and fewer still know that it was developed right here at Killington Resort. But inside the offices and planning rooms of Killington’s mountain operations complex, the K-3000 is spoken of in reverential tones. As Jon Kuehn, a veteran Killington Snowmaking Foreman who worked on the World Cup snow told me, “there’s no other snowgun like the K-3000, and no other snowgun I’d want to use under the tough conditions we faced before the World Cup.”

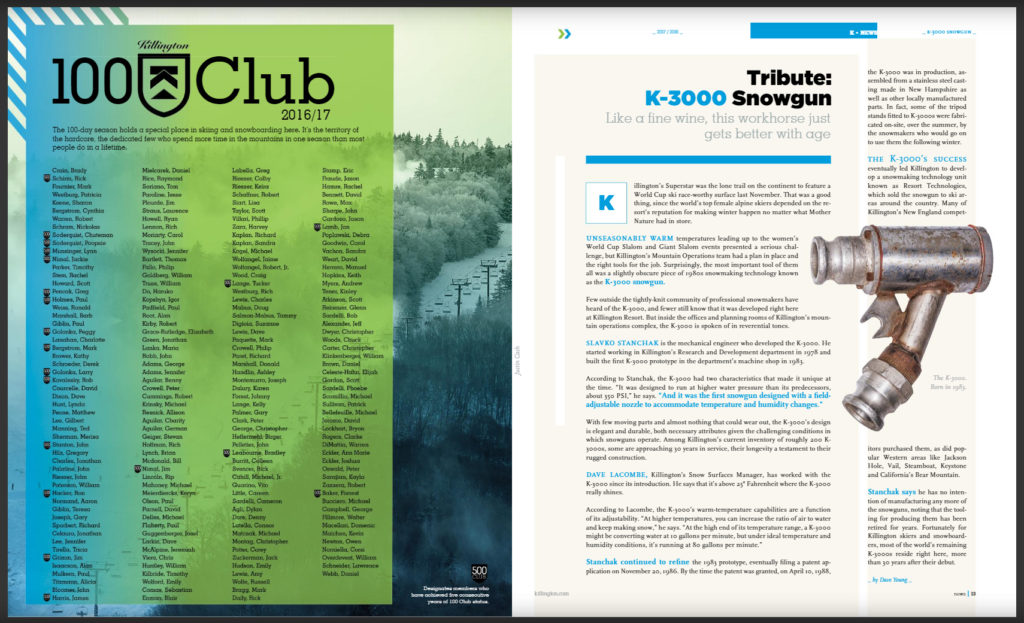

Slavko Stanchak is the man behind the venerable K-3000. A mechanical engineer who started working in Killington’s Research and Development department in 1978, Stanchak built the first K-3000 prototype in the department’s machine shop in 1983. According to Stanchak, the K-3000 had two characteristics that made it unique at the time. “It was designed to run at a higher water pressure than its predecessors, about 350 psi, and it was the first snowgun designed with a field-adjustable nozzle to accommodate temperature and humidity changes.”

Hidden away behind its brass nozzle and stainless steel casing, Stanchak explained, the internal chamber of the K-3000 is where the alchemy of air and water turning to snow begins. Inside the gun, high pressure water is introduced into the center of a cone of pressurized air. As the air and water try to squeeze through the adjustable orifice in the nozzle, internal pressure increases, turning the stream of water into a spray of fine droplets propelled into the cold ambient air, where they crystallize into man-made versions of Mother Nature’s snowflakes.

With few moving parts and almost nothing to wear out, the K-3000’s design is elegant and durable, both necessary attributes given the challenging conditions in which snowguns operate. Among Killington’s current inventory of roughly 200 K-3000s are guns of many vintages, some of them approaching 30 years in service, their longevity a testament to their rugged construction.

Dave Lacombe, Killington’s Snow Surfaces Manager, has worked with the K-3000 since its introduction. He pointed out that once temperatures fall into the teens, the differences between various brands and models of snowgun become less pronounced, so it’s at the upper end of the snowmaking temperature range, above 25 degrees Fahrenheit, where the K-3000 really outshines the competition. According to Lacombe, the K-3000’s warm temperature capabilities are a function of its adjustability. “At the high end of its temperature range, a K-3000 might be converting water at ten gallons per minute, but under ideal temperature and humidity conditions, it’s running at 80 gpm,” he said. “At higher temperatures, you can increase the ratio of air to water and keep making snow.” I wanted Lacombe to give me an upper temperature limit for the K-3000, but he explained that it’s not quite that simple. “There are so many factors that affect it, from the temperature of the water in the pond to the relative humidity, and even the moisture content of the air coming from the compressors. But anything above the mid-20s is K-3000 territory.”

The ability to keep producing snow as the mercury climbs comes at a cost though. The pressurized air that feeds a K-3000 is produced by diesel or electric compressors, and compressed air is the most expensive component of machine-made snow. Designed in the 1980s, when energy costs were lower, the K-3000 gobbles air at a rate as high as 600 cfm (cubic feet per minute). Contrast that with newer, high efficiency models—like the Snow Logic guns Killington recently invested in that use a consistent 8 cfm regardless of the temperature—and you’ll see why the K-3000s in the Killington’s arsenal are now reserved for situations where other guns simply cannot make the necessary snow; like a World Cup race at the end of a warm November.

Slavko Stanchak continued to refine the 1983 prototype, eventually filing a patent application on November 20, 1986. By the time the patent was granted, on April 10, 1988, the K-3000 was in production, assembled from a stainless steel casting made in New Hampshire as well as other locally manufactured parts. In fact, some of the tripod stands fitted to K-3000s were fabricated on-site, over the summer, by the snowmakers who would go on to use them the following winter.

The K3000’s success eventually allowed Killington spin off a snowmaking technology unit known as Resort Technologies, which sold the snowgun to ski areas around the country. Many of Killington’s New England competitors purchased them, as did popular Western areas like Jackson Hole, Vail, Steamboat, Keystone and Bear Mountain in California. Stanchak estimates that as many as fifteen resorts around North America have used the gun at one time or another.

Today, Slavko Stanchak considers himself retired, despite continuing to work as a consultant on snowmaking projects that interest him. Although he owns the K-3000 patent, which he purchased from the resort in the mid-90s, Stanchak told me that he has no intention of manufacturing any more of the snowguns, noting that the tooling for producing them has been retired for years. Fortunately for Killington skiers and snowboarders, most of the world’s remaining K-3000s reside right here at Killington Resort, where they continue to be the right tool for a certain job, more than 30 years after their debut.